After 2 years…

I’m back again! Lots of things have happened since the last posting, lots of things that I’ll probably write about one day™. But the topic of today is about an extraordinary opportunity I’ve had about joining an expedition with National Geographic and Lindblad Expeditions across the remote pacific ocean for 23 days.

The person responsible

Gratitude where gratitude is due, I wouldn’t have gotten this opportunity if it weren’t for the gracious invite of Adi Gajigan (last name pronounced ‘gah-hee-gun’). Adi is a National Geographic explorer and oceanographer at the University of Hawaii who studies (and is practically obsessed with) plankton and its importance to the planet. I have worked with Adi over the past year on using computer vision to classify and quantify plankton populations across various parts of the ocean, and when Lindblad Expeditions and the National Geographic Society reached out to him on an opportunity to sample across the remote pacific ocean aboard an expedition cruise ship, he generously decided to invite me along.

Left: Adi, Right: me; The second day, where we scoured the island of Palau in search of confiscated scientific equipment.

Alongside the two of us was also a high school teacher from New Hampshire, United States. Her name is Kelly Blais (pronounced Kelly Blah) and she was part of the National Geographic Society Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship, a scheme where examplary educators are invited aboard various voyages. The key intention here is for teachers to bring their onboard experiences into the classroom, allowing students and colleagues access to a higher level of geographic awareness.

Left: Adi, Middle: Kelly, Right: me; On Butaritari Atoll. PC: Kelly Blais

What is a National Geographic Lindblad Expedition?

Lindblad Expeditions is an ecotourism company, where they bring paying guests aboard one of their many capable ships to the most remote locations on the planet. Their primary destinations include places like the Arctic, Antartica, the Galapagos islands, and more. Guests get the opportunity to explore these places not only through the vessel itself, but also on smaller Zodiac boats that bring guests to perform land excursions or to observe wildlife up close. For the past 20 years, Lindblad has partnered with National Geographic to enhance experiences by allowing guests to explore alongside National Geographic explorers and photographers. There is a lot to this partnership and what the company does, and if you’d like to know more, Google is your friend.

The Journey

This is the path we took over 23 days:

Tracking data courtesy of Marco Pizzolato, a guest and now friend aboard the ship.

The image is not the clearest thing in the world, so for those who are more inclined to see the path we took, here is the tracking data that you can upload to Google Earth for a better view. The journey itself took us to the following islands in order:

- Koror, Palau

- Guam

- Magur, Chuuk

- Pohnpei (not that Pompeii), Chuuk

- Butaritari, Kiribati (pronounced Kee-ree-bas)

- Tarawa, Kiribati

- Niue (it’s its own freaking country with a population of 1,600. Crazy!)

- Aitutaki, Cook Islands

- Bora Bora, French Polynesia

- Tahiti, French Polynesia

I probably won’t do a detailed write up of each location (I’m not hardworking enough for that).

The National Geographic Resolution

The ship that I was on is the National Geographic Resolution - an exceedingly capable ship meant to traverse the Arctic and Antarctica regions. During my time there, it was helmed by Captain Martin Graser along with staff captain Iurii (Yuri) Bratash, first safety officer Efrem Ghirmai, ice navigation officer Finn Mackeprang (we saw no ice, obviously), and navigation officer Natalia Zameliukhina.

The National Geographic Resolution

Since I’m an engineer, here are some facts to geek out on:

- At the time of writing, this is one of three PC5 class icebreaking cruise ships on the planet. One other ship - The National Geographic Endurance, is also a Lindblad Expeditions ship.

- The ship uses a diesel electric drivetrain with dynamic stability. It consists of two V12 and two I8 engines, all turbodiesel, with a combined output of 10,000 horsepower. The engines were paired directly to generators, where electrical power is then used to power all the ship’s systems.

- Propulsion is handled through two rear-mounted azipods with 3-meter diameter stainless steel propellers, capable of going from as low as 15 RPM to (IIRC) 170 RPM. Two bow thrusters with a combined output of 2,000 horsepower allows the ship - together with the azipods - to be pushed from side-to-side without changing yaw.

- Due to the unique layout of the propulsion units, there is no need for anchors in most conditions as the ship is able to hold itself at a fixed location dynamically in winds of up-to 40 knots.

- There are three radar systems on the ship, of varying ranges and resolution. The one with the highest resolution is able to see birds sitting on water.

- The ship is made of 1 inch steel throughout, with the bow steel probably being thicker. This allows it to punch through ice as thick as 1 meter with minimal issues.

Throughout the journey, the ship burned about USD 1.2 million in marine diesel. That’s a whopping 35 tonnes of fuel a day, which works out to about 332 litres of diesel per person on board the vessel per day (there were about 120 people on the ship, staff included). That’s a very sobering number, and while I don’t have anything greenwashing to say, I thought it’s important to put it out there.

While we were on the ship, we were posted in the Science Hub. A very cool venue where we had surround screens and enough desk space to host all our equipment. Intrigued guests could come in at any time and ask questions and engage in the science that we were doing onboard.

The Science Hub aboard the National Geographic Resolution. PC: Kelly Blais

Open Bridge Policy

The ship operates an “open bridge policy”, a policy where anyone at any time is allowed on the bridge to observe crew activity. This meant I was on the bridge a whole lot - you can’t blame me, lots of things to geek out about there.

Wide angle view of the bridge and one of the drones in the bottom left corner (that I helped fix 😬)

Some instruments on a side control console.

Navigating into Pohnpei (I think?).

How to park a ship step 1: look cool.

How to park a ship step 2: turn some knobs.

Wildlife

Jellyfish Lake, Palau

Our first intended encounter with exotic wildlife happened in Palau, where we swam in Jellyfish Lake. Jellyfish Lake is home to the Golden Jellyfish and the Moon Jellyfish. The Golden Jellyfish is endemic (science speak for unique) to this lake. Both jellyfish have evolved over several thousand years to have no stingers, which means they are safe to swim with. So naturally, we got to swim with and touch them (they just felt like agar-agar underwater):

The Moon Jellyfish

The Golden Jellyfish

There was also a Cardinalfish, I found this interesting because I could only see these in aquariums back home in Malaysia.

Cardinalfish.

Manta Ray, Palau

We also saw a Manta Ray. I’m not sure if there were more than one that day, but this is the one we got a close up of:

Probably the most graceful creature I've ever been up close to. Along with an indication of how absolutely clear the water was.

A video of the Manta Ray, in case the previous picture just looks like a rock to you, **ahem sis**.

Humpback Whales

On our way out of Aitutaki, we witnessed a small pod of humpback whales. According to the naturalists, it was a mom and calf pair with an escort male, with the calf supposedly born not too long ago. I could barely tell there were 3 humpback whales in the water. For me, this was a bucket list item ticked off before it even entered the list.

A trio of humpback whales we saw.

Notable Mentions

These are wildlife creatures that I didn’t have the chance to get on a digital media format, but nevertheless will record here for my memory:

- Flying fish, arguably saw very late into the journey but very memorable

- Black tip reef sharks, absolutely sexy

- Cuttlefish, apparently super rare to see while snorkeling

- Stingrays, yes, I swam with them

- Sea cucumber, like a big shit

- Pilot Whales, a group of about 150 - possibly 3 pods

Throughout the journey, we had about 10 sessions where we could snorkel, and all of them were execellent - no pollution, crystal clear water, teeming with wildlife. Here are some of the videos I have, these were taken with my phone at the time (Samsung Galaxy S10) through a plastic pouch. They look much better in person.

Snorkeling at Palau. Very bleached coral due to global warming.

Snorkeling at Bora Bora. Sea cucumber in the first few seconds.

Moments

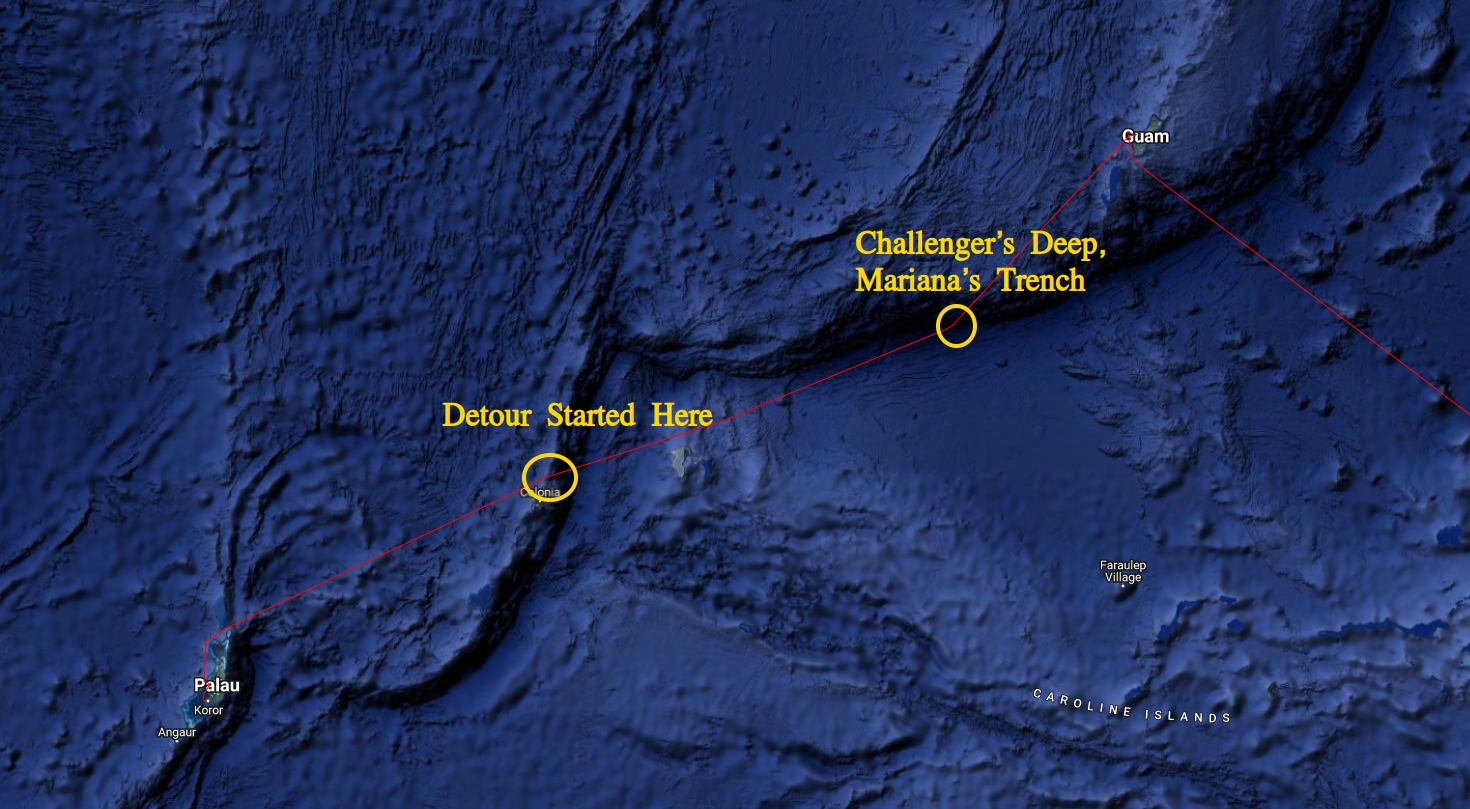

Swimming over Mariana’s Trench

We had an opportunity to perform a small detour over Challenger’s Deep, Mariana’s Trench when transiting from Palau to Guam. Since the conditions were favourable and because our ship could hold position without dropping anchor, blue water swimming over the Trench was possible. This was also another bucket list item ticked off before it entered the list. Unfortunately I don’t have any pictures of me over the Trench.

Where Challenger's Deep is relative to our journey.

Blue water swimming over Challenger's Deep, Mariana's Trench.

Visiting Magur, Chuuk and interacting with locals

In between the transit from Guam to Chuuk, Captain Martin made the impromptu decision to visit one of the isolated islands along the way. This necessitated a whole lot of work from the expedition staff (looking at Andy and Alexandra) to obtain the necessary green lights to make it happen. Ultimately, we got what we needed, and we were allowed on shore via Zodiacs.

The island’s name is Magur, and it hosts exactly one primary school and church. Many amenities were non-existent - no power and sewage grids and don’t hope for roads. Instead, people there survive via subsistence farming - farming only what they needed and living off the land and sea. I found it impressive that one of the local houses had a Frigate bird as a pet! Apparently birds are really easy to imprint on? I certainly wouldn’t know.

What struck me more was the lack of common clothing. I’d imagine this was the case because everything needs to be imported. Because of this, the locals mostly wore what I would describe as “sarongs” and surf pants. I won’t share pictures of the locals here - I didn’t take any, but here are pictures of what the island roughly looks like.

Views around Magur Island.

The view out from one of their beaches.

Tamed Frigate bird on Magur Island.

Visiting such a remote island as an outsider is always controversial. Personally, it was a bit uncomfortable to me at first, especially since I was raised in a country where western colonization played such a large role. However, I’d like to believe that we approached the subject in as neutral a manner as possible. If anything, I’d like to rephrase the words of expedition staff and National Geographic explorer Jennifer Kingsley - “we’ll try our best to make this as cool an opportunity for them as it is for us. They don’t get lots of visitors around here, so hopefully we give them an experience where they can look back and say ‘wow, that happened!’.”

Experiencing the calming dulldrums at the planet’s thermal equator

The Intertropical Convergence Zone, AKA dulldrums, is a zone over the thermal equator known for its monotonous windless weather. Expedition staff Joe Holliday can probably tell you everything about it. This was mesmerizing to me because I have never seen the ocean that calm before, it was practically a sheet of glass. Since we were travelling South into the thermal equator at the time, the ocean just got calmer and calmer as the day passed. Needless to say, I probably spent the most time on deck this day, it was ✨magical✨.

Sailing over the planet's thermal equator.

Water's so calm you can see the ship's reflection. This is the OCEAN we're talking about.

Giving a talk on Artificial Intelligence to guests and expedition staff

I gave a talk aboard the ship about AI, where it came from, where we are, and where we’re going.

A picture taken at the end during the QnA session.

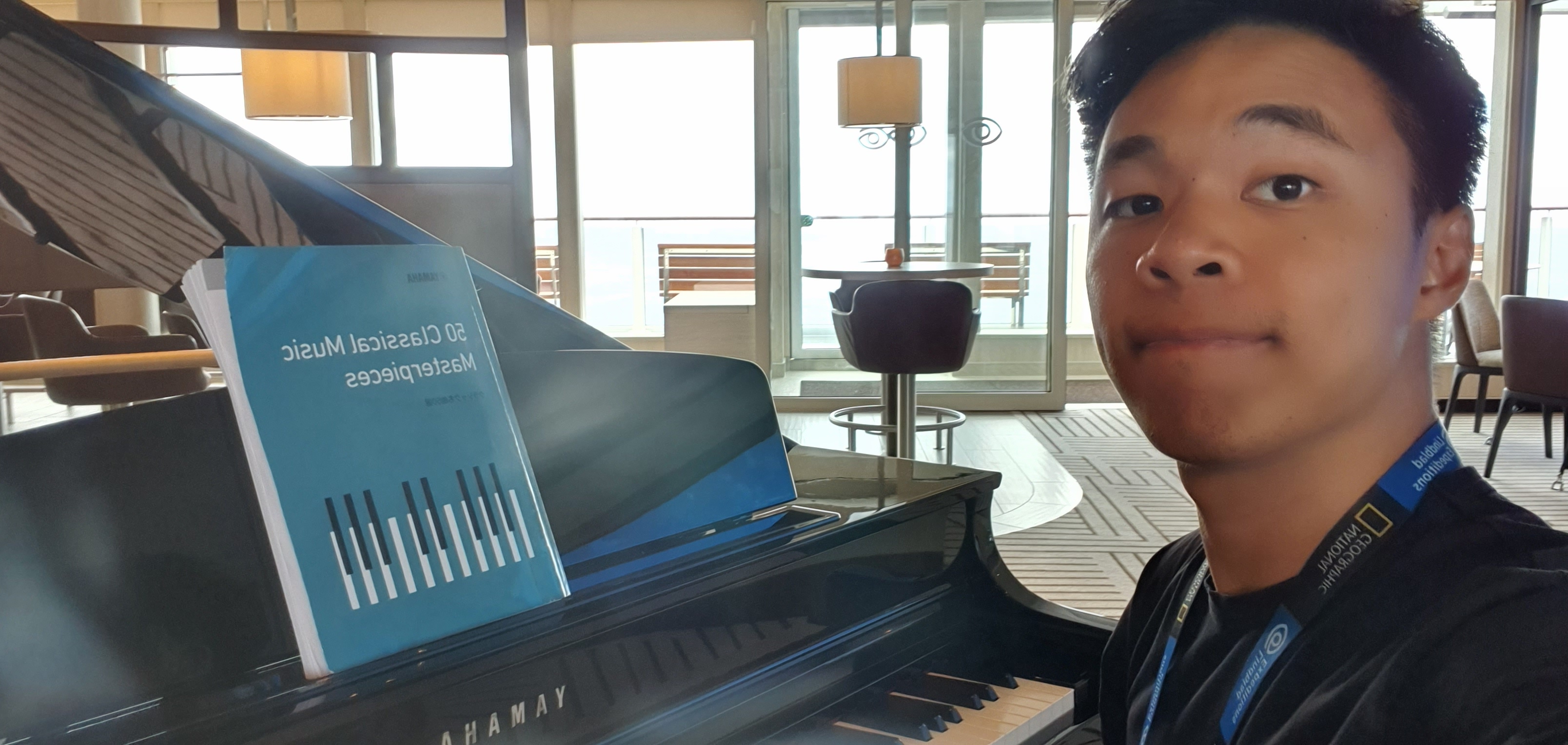

Playing the piano abord the ship

I played the piano aboard the ship. This was pretty cool to me. Songs I played the most:

- Little Talks - Of Monsters and Men: I liked the lyric: “This ship will carry our bodies safe to shore”

- Ghost - Justin Bieber

- A bunch of other Coldplay songs

- Raining in manilla - Lola Amour: Played a minor-ed version

There were also several song requests from the hotel staff onboard, but my piano skills weren’t good enough to sight read or play-by-ear their requests.

Playing the piano on deck 8 of the ship, just outside the Science Hub.

A wider angle shot. PC: Joseph Holliday

Visiting the Marae Taputapuatea in Raiatea

The emotional highlight of the trip for me happened here. Raiatea or Ra’iatea (pronounced Rah-ee-uh-tee-uh) is an island near Bora-Bora, just west-north-west of Tahiti. It is known traditionally to the Māori people as Havai’i (not to be confused with Hawaii). On Raiatea itself is Taputapuatea marae (pronounced Ta-pu-ta-pu-ah-tee-ah ma-ray). A marae is a communal sacred place that serves religious and social purposes in Polynesian societies. It is a rectangle piece of land that is bordered with stones and has a floor made also of stones. Supposedly, each stone comes from a different place in the entirety of Polynesia.

Entrance into Raiatea.

Where the ship was parked, dynamic positioning is amazing.

Taputapuatea marae is considered the central temple and religious center of Polynesia. In Jennifer Kingsley’s words, Taputapuatea roughly translates to sacred sacred land of sacredness. So clearly, this was important to the Polynesians. So important in fact, that under the usual circumstances, no outsider was allowed into the compound.

Contrary to the usual circumstance, we had Polynesian master navigator Teuatakiri Pittman, AKA Tua Pittman, AKA Tua, with us. Beyond just being a living legend, Tua has many roots and is very well respected across Polynesia. I won’t do a complete write up on him - Jennifer Kingsley is already working on that, read her book when it comes out. For the purposes of this story, one of Tua’s many friends (really more like a brother) is a man of royal Polynesian descent. This man’s name is Matarae, and through a sacred communication with the heavens, the spiritual gates of Taputapuatea could be opened to us outsiders.

The meeting between Tua Pittman and Matarae, with the first marae in the background. Jump to the end to witness a brotherly hug.

We got to enter both(!) maraes at Taputapuatea that day. The first was a bigger compound of slightly less cultural significance, at the far end of the marae was a shrine of sorts, with various tea leaf branches layered neatly. The second compound was the supposedly more significant one, with a large white stone in the center. Tradition has it that the son of a polynesian creationist god was born at that very stone. I’m no historian, so I won’t try to describe any more than this for fear of mentioning something completely wrong and getting cancelled. Remember, Google is your friend.

The first marae we entered.

The shrine at the first marae.

No shoes were allowed within both compounds, a similar status quo to entering temples from other cultures. Going from wet grass outside the compound to dry stone within the compound, the first thing I noticed was the sun-baked warmth from the rocks which made up the floor. The second thing I noticed was the incredibly sombre atmosphere inside the compound versus the outside, a similar atmosphere when entering any temple or center of cultural significance, despite the marae having no walls or ceiling. Here, Tua chanted a blessing in a Polynesian tongue for Assistant Expedition Leader (AEL) Alexandra Kristjánsdóttir, Hotel Manager Juan Sebastian, and Captain Martin, blessing them with safe travels on all future voyages. Right after the ceremony happened, a light drizzle started and two white birds took off from the nearby mountain. We were told that this symbolizes that the heavens have accepted us for who we are. It was at this point that I asked local astrophysicist and UC Berkeley professor Steve Croft, “do you still think the universe is fundamentally random?”

At the second marae, the more significant one, everyone got a chance to touch the stone. This action is meant to symbolize a connection between you and all your ancestors of past, and all the spirts of your future. If you asked me what I felt, I felt that I had no connection to my past beyond my grandparents and I have no idea where I’m going in the future. But maybe that’s because I’m just 26 and a sojourner in life. Anyway, here’s the visual content that you really came here for.

The second marae, with Tua Pittman at the entrance.

The actual stone at the marae. With AEL Alexandra Kristjánsdóttir and Marco Pizzolato having their moment.

People

All of the people aboard the ship have been incredibly inspiring, and I think this will be the aspect I miss the most. From Captain Martin Graser with his can-do attitude when dealing with a USD 150M ship to the hotel staff striving to deliver the best experience 110% of the time, here are some of the people I want to give special attention to.

- Captain Martin Graser: I can see why he’s captain. Playful and non-chalant when necessary, but strict and regimented when at the helm. Aside from that, he’s also incredibly logical with his thinking, and not afraid to call out bullshit. Also let me have a hand at fixing both ship navigation drones.

- Andy Wolff: Incredibly detail oriented but with copious amounts of empathy under the hood. I admire his commitment to his work and sometimes wish I could see him just swear a bit because of the amount of stress he’s under.

- Tua Pittman: Basically the best uncle to have on the ship. Always delivers the best jokes at the right time but also has a very protective aura? Kind of motherlike if I’m honest. He can also captain a sailing canoe around the world with zero instruments 🤯.

- Jennifer Kingsley: There is so much to learn from Jenny. And I don’t mean from a technical perspective. Jenny excels at placing herself at the right social altitude for the breakdown of artificial emotional barriers. She doesn’t portray herself as higher or lower than anyone she talks to, and has an ability to always ask the right questions. She’s also a remarkably good storyteller. These two traits make it really easy for deep, meaningful conversations to occur. The one lesson I will take away is to learn to ask “so, tell me everything”.

- Joseph Holliday: From a social perspective, I would describe Joseph as a Christmas tree, with all the lights and baubles to portray the warmest, most radiant mood, enough to make you believe it’s actually a Holliday 😉. But below that cheery exterior, Joseph is two things: incredibly smart and knowledgeable about Earth and all (I’m not kidding) of its processes, and also incredibly attentive to social patterns and connotations around him. He’s also really caring about the people around him, and has a glowing passion for educating.

- Nitye Sood: An absolute gigachad of an inspiration. Nitye is the most humble person I’ve met on the ship. He also happens to have balls of steel - he films wildlife and has had many close encounters with King Cobras, wild dogs, Rhinos, and other mind-bending creatures. My takeaway lesson from Nitye is to always follow your dreams - he spent about 10 years being constantly broke before his work started taking off. If I don’t get to work with him in the future, at the very least I hope to meet again one day over some Chai and ask “what are you up to next?”

- Marco Pizzolato & Alexandra Kristjánsdóttir: The couple who became more comfortable with PDA throughout the expedition 😛 (it never got unbearable I just poke fun). Alexandra is a very dedicated worker who’s also a vegan and cares for the environment but is also very fun to be around (how does that work?). Marco is a software engineer who also happens to be really open to saying “I don’t know” and learning about new things. Both very fun to be around.

- Juan Sebastian: JuanSe’s story is a complicated one - I won’t describe it here for privacy’s sake. But what I admire from him is the ability to always put on a smile and to look forward. His faith in “figure it out later” is admirable. Outside of that, as the hotel manager, he also always aims to put 110% into his work, always attentive to everyone’s wellbeing. He also arranged for us to have Banoffee Pies twice!

- Cristian Moreno & Brett Monroe Garner: The two divers with very different backgrounds. Cristian is a fighter of justice at heart, and you can see that he will put his life down if it means fighting for a better cause. Brett is a very underspoken character with down-under humour, but also very fun to be around if you’re able to ask the right questions.

- Santiago Imberti: I have never EVER seen anyone as dedicated to one specific topic as Santi. Santiago is a birder, in that he observes and identifies wild birds in the wild. Throughout the expedition, I have not seen Santi take a break from birding whenever there was a possibility to do so. He’s always on top deck under the scorching sun, or out in the bush looking for birds. Frankly I am unable to wrap my head around this obsession, but if everyone in the world had at least 10% of Santi’s commitment towards anything, it’d be a much better place.

- Michael Nolan: Michael is a National Geographic photographer who is exceedingly adept at figuring out what makes a good photo and what doesn’t. All of his pictures incorporate very fine details and decisions that make them stand out from the norm. One example is taking picture of a person in a hat made of leaves in such a way that both the subjects eyes are framed by the leaves from the hat symmetrically. His skill with the camera is only matched by his knowledge of undersea creatures and their ways (he was the one who immediately identified that there were 3 whales) in the water. Outside of talent Michael is kind, well spoken, and overall a totem of knowledge to be around.

- Lori Andrus & Steve Croft: My favourite husband and wife duo on the ship. Lori and Steve have an uncanny ability to read each others’ minds that sets the new standard for what I think relationships should be (uh oh, I know). Lori, being a lawyer, is very good at directing the right question at the right place and getting the right person to speak at the right time. Steve is an astrophysicist from UC Berkeley and what I would describe as a grown up, very successful, very knowledgeable geek. Love them both, hope to see them again someday.

A group picure of all expedition staff. Yes it's not perfect. No I don't care.

Other Notable Points

The cost of the expedition is $35k at the low end. Here are just some of the things that I think people should know. We had three course meals for lunch and dinner everyday with white and red wine selections. Breakfast is a buffet with an egg station. Tea time is served everyday with an assortment of food (we had sushi one day). There was also a cocktail hour with any cocktail you can possibly imagine. There was a 7 course introductory dinner at the beginning. Your room is cleaned once every two days and they use the highest thread count bed sheets I have ever seen. Here are pictures:

Sushi spread for tea time

Food onboard.

The room that me an Adi shared. This is a staff room and not what paying guests experience.

Disclaimers

I have over 40 GB worth of images and videos, ask me if you want to see anything in more detail.

All thoughts and opinions are mine and do not represent that of National Geographic, Lindblad Expeditions, or any of their staff and guests.